Should You Invest In Dividend Stocks Or Pay Off Debt?

By

Josh Wilson

As your income rises, you might face the happy dilemma of what to do with extra cash. If you are a somewhat conservative investor, you might be tempted to purchase stocks that pay regular dividends.

A stock’s dividend yield is the annual dividend amount divided by the stock price. Owning a portfolio of dividend stocks, whether individual shares or through a fund, is a way to supplement your monthly income with a fairly dependable cash flow.

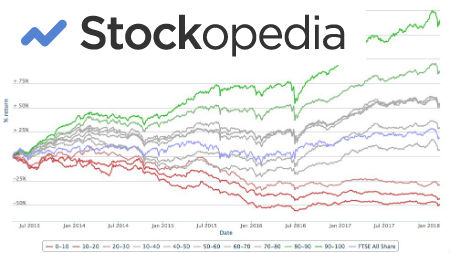

You can produce an dividend yield through purchasing ETFs. Seeking Alpha picked the five leading dividend-stock ETFs based on yield and expenses, and their yields ranged from 2.01 percent to 3.17 percent. Total return on these stocks is the sum of dividends paid and price gains (or losses), and in bull markets you might easily receive a double-digit return.

The allure of dividend-stock income might seem more attractive than paying off debts, but the best course of action should be based on quantitative information, not emotion. And the basic data point that can help you decide is the after-tax benefit.

The Tax Angle

To understand the tax implications of your spending decisions, consider the following:

1. Your marginal tax rate is the tax percentage you pay on your last dollar of annual income. For 2017, the marginal rates are 10, 15, 25, 28, 33, 35 and 39.6 percent, depending on your income.

2. The after-tax value of income is equal to the gross amount multiplied by (1 – marginal rate). For example, if you are in the 28-percent tax bracket, the last dollar of after-tax income is worth $1 x (1 -0.28) = $0.72.

3. Dividend paid by most American stocks are “qualified,” which means they are eligible for lower tax rates. For 2017, the qualified rates are 0, 15 and 20 percent, depending on your income. In other words, you get a tax break by investing in qualified-dividend stocks.

4. Mortgage interest is tax deductible. The value of the deduction is tied to your tax bracket. For example, if you are in the 28 percent bracket, your mortgage interest deduction reduces the after-tax cost of your mortgage interest payments by 28 percent. If you pay $5,000 in mortgage interest for the year, the after-tax cost to you is $5,000 x (1 - 0.28) = $3,600.

5. All other interest costs are not deductible, and therefore make no difference to your after-tax income. This means that you get more benefit by paying down non-mortgage debt ahead of mortgage debt, because the former is costing you 100 cents on the dollar.

The Cost of Debt

In the summer of 2017, the national average interest rates have remained moderate:

· Mortgages: 3.79 percent for 30-year fixed rate.

· Credit cards: 16.69 percent for variable-rate credit cards.

· Personal Loans: 2.19 percent to 35.99 percent for fixed rates.

· Student loans: The current rate for federal student loans is 4.45 percent. The average fixed and variable rates on private student loans is 9.66 and 7.81 percent, respectively.

A Worked Example

Assume Joe receives a tax-free inheritance of $5,000 and wants to use it wisely, either to buy dividend stocks or to pay down debt. Joe is in the 28 percent bracket, has a mortgage, credit card debt and private fixed-rate student loans. Joe wants to know which course of action will provide the biggest financial benefit in the next 12 months. Here are his options:

1. Buy dividend stocks: Joes puts $5,000 into a dividend-stock fund paying 3 percent after deducting fees, equaling $150 per year. The tax rate on these dividends is 20 percent, so the after-tax increase in Joe’s wealth is $150 x (1 - .20) = $120.

2. Pay down mortgage: Joe reduces his 3.8-percent fixed-rate 30-year mortgage principal of $150,000 by $5,000. A mortgage calculator, which accounts for the effects of compounding, shows that Joe will save $280 in the first year.

But the after-tax benefit is reduced by the tax-deductibility of his interest payments, since he loses that deduction on the amount paid down. Therefore, applying Joe’s 28 percent bracket to the $280 savings, Joe’s after-tax wealth increases by $280 (1 – 0.28) = $202.

3. Pay down credit cards: Joe pays off $5,000 in credit card debt. He was paying 17 percent interest on his cards. His saving is $5,000 * 0.17 = $850.

4. Pay down student debt: Joe’s $100,000 in student loans charge 7.8 percent interest. The loan term is 15 years. A student loan calculator shows that Joe will save $537 in the first year.

Conclusion

In our example, the greatest benefit comes from paying down the highest-rate debt you owe. Investing in dividend stocks is the least remunerative, at least in the current economic conditions. In a hotter economy, you might earn a higher dividend yield, but you could also pay higher interest rates.

You might purchase dividend stocks in a tax-deferred retirement account, such as a traditional IRA, thereby increasing the short-term value of the investment. In our example, Joe would earn $150 instead of $120 after taxes, but that’s still less than the benefit from paying down debt, and it ignores the fact that you’ll have to pay your marginal tax rate (not the 20 percent qualified dividend tax rate) on withdrawals.

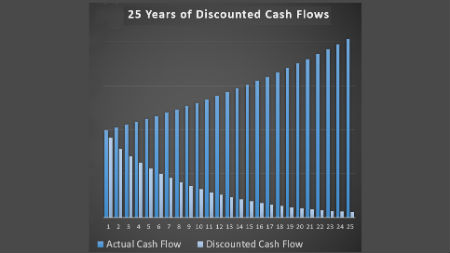

Bear in mind that this analysis doesn’t account for capital gains on your dividend-paying stocks or dividend growth. Some stocks (such as dividend aristocrats) have grown their dividends for many years in a row.

You don’t have to pay taxes on capital gains until you sell the shares. Long-term capital gains rates (for stocks held longer than one year) are the same as those for qualified dividends.

You can read more from Josh on his own website.

Got a BURNING dividend question for 6-figure dividend earner Mike Roberts?

What is it that you really want to know about investing?

Submit a query and Mike will write a page in response.

PLEASE NOTE - in accordance with our terms of use, responses are meant for education / interest only. We do not give specific financial advice.